My Childhood

I was born so long ago, that only people of my age can know what it was like to live in certain parts of London, which has changed so much. By contrast, in rural villages and small towns, there's hardly been any change at all. Science and technology has advanced so rapidly and the great changes mean that much of what life and the environment were like has been forgotten, and become history. Children today hardly know what it was like for their grandparents.

My parents lived in a street

in the parish of Spitalfields in the east of London. Spitalfields church is

famous for its architecture as it was built by Hawksmoor, an associate of

Christopher Wren. Our home was at the very top of a tenement block in a small

flat with one bedroom a drawing room, kitchen and toilet. The building was

owned by a company representing a philanthropist who wished to house the poor

people at very cheap rent or even no rent at all for the very poorest. The

whole street was taken up by similar types of buildings, some even without

toilets. Each floor or landing as

they were called, contained four flats, and they had to share one toilet and

one rubbish slot. Some flats housed between two and eight people and the only

running water was one cold water tap in the kitchen. The kettle on the gas

stove was the only way to get hot water so people had to go to the Council

baths for a decent wash. The only light was the gas mantle, which was operated

by a gas meter. Pennies were needed to feed the meter to keep the light on.

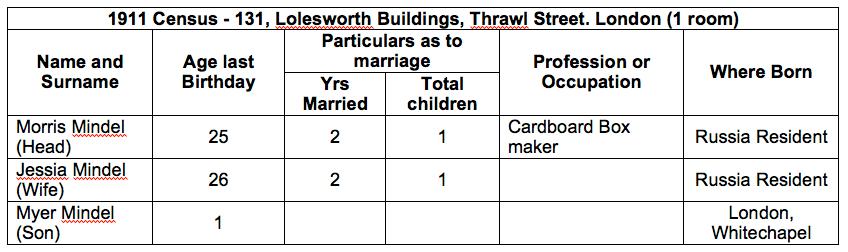

(The address of the Mindels shown on the 1911 Census is 131,

Lolesworth Buildings, Thrawl Street. London.

We lived so high up, I guess my mother was thinking was she was about to have a heavenly child. She already had two boys, and was hoping for a girl. The doctor and the midwife who came to attend to my mother didn't think it so heavenly after climbing all those stairs and becoming exhausted. Water had to be boiled to wash mother and baby. The light went out and the doctor was the only one with pennies for the meter. It looked as though I was going to be a troublesome baby. Somehow, even though she wanted a girl, she liked me and I liked her, and it remained that way for the rest of our lives. But as the song says 'you always hurt the ones you love' and there were times that happened.

My brothers were going to school and my mother had been working odd jobs until the last minute. She took care of me until I was able to go to nursery school, then she went back to work. Work was difficult to find and my parents could never be late for fear of losing their jobs so she could not usually take me to school so I went to the nursery with a boy a little older than me. My brothers did take me sometimes if the other boy was not around. It was fortunate that the nursery was close by.

As I grew older, I was able

to understand what was going on around me. The street in which we lived was

near Flower and Dean Street, which was the most notorious in a very notorious

area. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flower_and_Dean_Street.) Some decades before my time Jack the Ripper had

stalked that part of London and one of the murders had been in an alley off a

street close to ours. Many books have been written about that killer but there

is still confusion about who he was, what he was, and where he came from. He

has never been found. (This historic map shows Flower

and Dean Street with a pink highlight and the adjacent Thrawl Street and

Lolesworth Buildings. Locations of 3 possible Ripper murders are shown as red

dots.)

One end of our street led to the main road, the other was where all the unsavoury action took place. On one corner there was an infamous public house that was known to sailors from all over the world. When their ships came to London they made straight for the pub. On the other comer was a ladies shelter, full of prostitutes. The sailors were happy because the drink was cheap, as were the women, and the pub was always full of locals and others. Almost every night there were drunken fights and there were always thieves around to rob the drunks. In the fights, women were often involved and they could fight as well as the men.

The police were well aware of what took place. A policeman was always on duty close by. In those days the police didn't have the facilities that came later. In fact the local station didn't have a car or van. The policeman carried a truncheon and a whistle. As soon as he was needed for some reason he would blow his whistle and signal that help was required.

Very often, after fights, someone was lying on the floor unable to move, either drunk or knocked unconscious. With no transport available, the only way to take the bodies to the police station was by a barrow. When the bodies arrived at the police station, or the Nick as it was called, they were put into cells to recover. The police, always looking for a peaceful life, got rid of them as soon as possible. In the morning they were given some breakfast, made to pay a fine (if they had any money) and sent back to their ship or wherever, they came from.

The police knew that they had to prepare for another repetition of the same, but were just hoping to be left alone. There were many other things they had to do. Our neighbours, in the flat next to ours, were a policeman and his family. We were all very friendly and helped each other. In fact my mother acted as a midwife, when the policeman’s eldest daughter gave birth to a baby, unexpectedly. But not everything ran smoothly. The policeman's wife liked gin and sometimes became drunk, but the effect was not too bad if you didn't mind listening to off-key singing. Her husband was away quite frequently as he was stationed on the other side of town.

Our local copper - his name was Tom - was both liked and disliked, by me and all the other kids. When he was on duty around our streets, everyone knew him and he knew them. He was always smiling and had a kind word. In return he often enjoyed a cup of tea offered by one of the tenants, especially on cold days. Of course he couldn't be seen drinking his tea in the open; he just stood inside the gateway, in case the inspector came by. In truth although the inspector didn't know about the tea, he would have probably liked to join him. How life has changed! Why doesn't the television show the program "Dixon of Dock Green" anymore - with the loveable constable played by Jack Warner? I suppose it would be ignored by modern youth, who much prefer violence.

We kids were playing cricket in the street one day with improvised wickets made of old wooden boxes. Tom saw me batting and came over and said we had to stop because it was dangerous - a car could come along and cause an accident. That would have been very unlikely as hardly any cars were around in those days but the law is the law. We stopped playing for a few days but we soon decided to recommence, this time with a look-out. In spite of that he came by once and caught us. He beckoned me with his finger and said, 'I thought I told you to stop playing in the road'. With that he gave me a little clip around the ear. I barely felt it. I shed tears of shame, but only for being caught. If this happened today, the parents of the boy would sue the police for thousands and the copper would lose his job. Constable Tom closed his eyes to our playing in some part of another street nearby which was much safer. The tenement building did have playgrounds, but ball games were disallowed, because of the windows constantly being broken.

As I grew older and went to school, I became friendly with different boys and our interests broadened out. We ventured into new environments, and started to learn more about life. I usually got home from school about teatime. My mother came home later. Of course she had to climb all those stairs. She came through the door and flopped into the nearest chair. I said "Mum what's the matter you look ill, because you’re working too hard." She replied, "No son it's not the work, I've got bronchitis." I hadn't got a clue what bronchitis was. I also found she was suffering from varicose veins and came to understand that she needed help somehow.

I listened to the family talk and I could tell that there were great difficulties which all seemed to be because of the lack of money. Being so young I couldn't see a way that could help. But the unexpected plays tricks, sometimes good and sometimes not so good. A neighbour was having some trouble with her hip and could hardly walk. She saw me as I was about to go down and play. She asked me to go to the baker and buy a loaf of bread. I was happy to go as I had done this so many times for my mum that I could do it backwards. When I returned with the loaf she was pleased so she gave me a penny. A penny in those days was worth much more than it is today. I was very happy to get a penny and she was happy to have me go up and down the stairs, I said that I would do the errand anytime she needed me. I was getting three pennies a week while she couldn't walk. The kind lady had friends in the other flats who visited her and she told them about me. They said that they could use me sometimes. Within a few weeks I was earning between six pence and a shilling, I am sorry to say I cheated on my mother sometimes and spent a penny on some sweets and chocolate. Fortunately there was no tax to pay. I don't know how far the money went to meet the family’s needs, but my mother was feeling much better, not just for the money, but because I was thinking about helping her.

My father was a very clever and well read man. He understood the need for learning and having a good education. He wrote articles in papers sometimes, but couldn't earn much that way and so he had to find work to earn more if he could. Unfortunately, he had many handicaps. He was very cumbersome and had slight Parkinson disease, when I tried to play ball with him he had not the slightest coordination. He loved to listen to lectures by famous professors and scientists. I know that Bernard Shaw was one of his favourites. He used to take my brothers with him on Sundays and then me later. I believe the place was called Conway Hall. It was a freethinking society, non religious.

My dad gave lectures and held discussion classes in the evening Education Institutes and continued to support The Workers Circle by reading and writing for people who were illiterate. However, none of this was paid work and his contribution to the family finances was very little. Yet he was exceptionally kind. If he saw anyone destitute, he would share his pennies. Many of his friends were writers, poets and intellectuals. When he became older and I was available I would drive him to their meeting place on a Saturday afternoon.

As I got a little bigger and stronger and attending school, I became quite good at all sports but especially soccer. In the Inter Schools Division, in the local borough, the sports masters got to know me and selected me to play against other boroughs with the possibility for playing for the London Schoolboys, in my age group. With all the flattery I received I imagined that my future lay in professional football. This Illusion caused me to act stupidly. I didn’t concentrate on my school work as I should have. At one time I was top of the class but as I lost interest, because my thoughts were mainly on football, my position in class got lower and lower.

I was supposed to stay at school until I was sixteen and prepare for a place in university but I found out that the minimum age for leaving school was fourteen. To the horror of my father, I left school on the day I became fourteen. I had to make a solemn promise that I would continue with my education by attending evening classes.